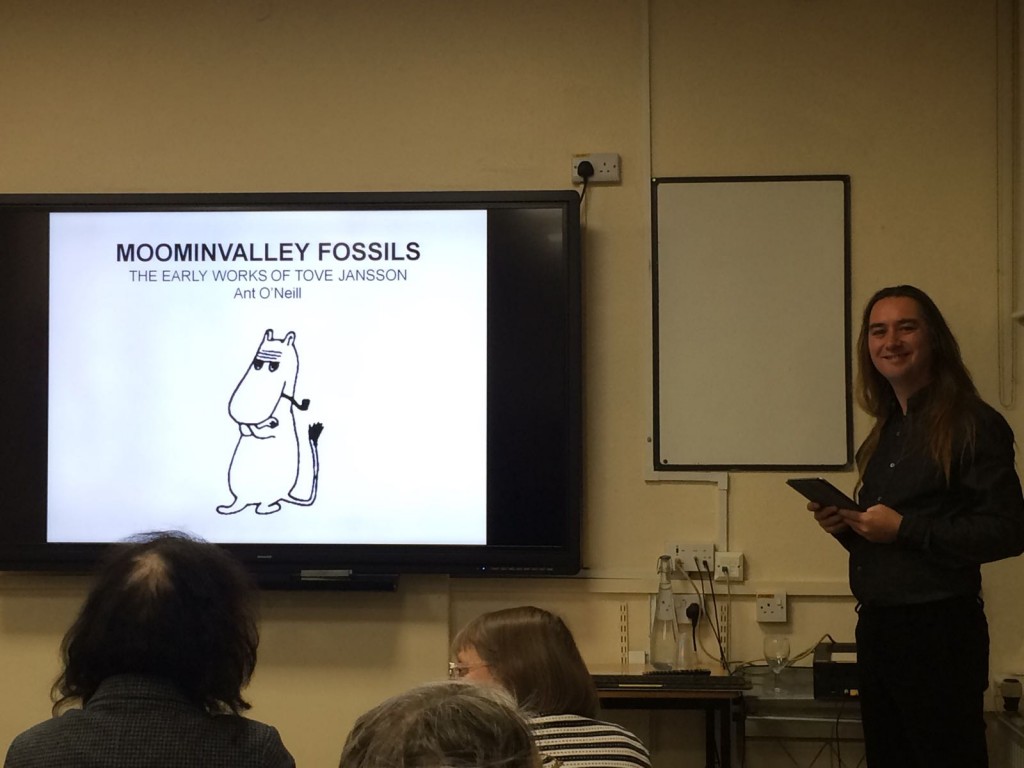

With the advent of the the Tove Jansson exhibition at Helsinki’s Ateneum and its subsequent tour of other cities, Jansson’s non-Moomin work was finally given the front and centre stage position it deserved. It’s been well documented that the success of the Moomins overshadowed Tove’s other works, often to her frustration. But what of Lars Jansson?

Tove’s brother took up the helm of the Moomin comic strips after Tove’s contract ended, and he drew them for fifteen years; he also collaborated on the TV series and the creation of Moominworld in Naantali. But Lars also had other strings to his bow.

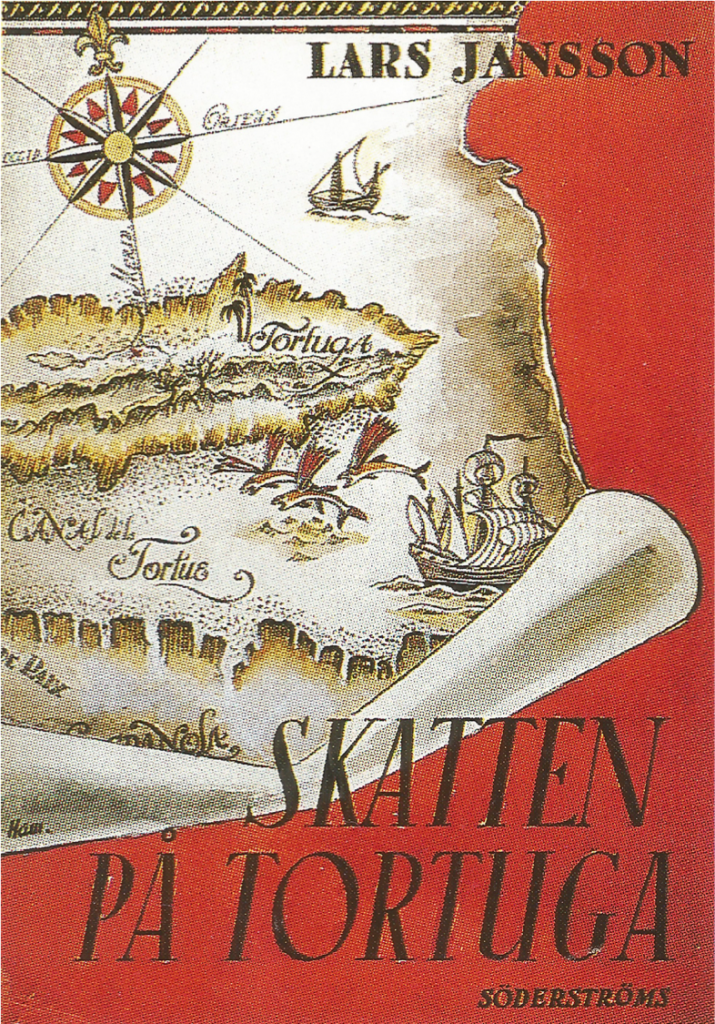

Between 1941 and 1967, he wrote eight novels. The first, Skatten på Tortuga (The Treasure of Tortuga), was written and published when he was fifteen. The story of two boys finding a pirate’s treasure map and stowing away on a boat to the dread island of Tortuga at first seems to be typical teenage wish-fulfilment. But even at the age of fifteen, Lars had a gift for writing, and the structure, pacing and storytelling are surprisingly grown-up.

Less surprising is the fact that a number of the devices employed would find their way into Lars’ later Moomin comics. The Moomins often deliberately or accidentally went on long sea voyages and in fact, Tove and Lars had discussed the possibility of stowing away on a ship themselves – a likely inspiration for the story.

The image above is the cover of the book – this was drawn by Signe Hammerstan-Jansson and hasn’t been seen since 1941.

I’ve been working on the translation of Skatten and here – for the first time in English – is the prologue….

PROLOGUE

In the darkness of a small room of a castle in the middle of the Scottish moors, sat a lone man at an oak table. The room was simply furnished in the old Gothic style, with oak-panelled walls lit by a single lancet window. The floor was covered by a soft carpet, patterned only by the shadows thrown from the heavy iron chandelier.

No paintings adorned the walls. Instead, a variety of guns and weapons revealed the man for what he was: one of Morgan’s Buccaneers, and one who had worked – fought – his way to the dubious top of his profession: a pirate captain. Everything about him spoke of his chosen career, from his wooden leg to his flaming, wild eyes that had the expression of a hunted animal and, despite his fine, aquiline nose, his bushy black eyebrows and bearded visage did little to beautify him.

A half-empty schooner of rum lay on the table in front of him, next to a map. Outside, the wind shrieked as the storm battered the heath, and a loose copper grate rattled somewhere up on the roof. The watchdog howled and tore at its chain. Were those footsteps he heard on the gravel? The man shuddered and looked around, memories of times past chasing each other through his head. Ah, that necklace of black diamonds. Would it never cease to torment him?

He should not have stolen it.

But he was a pirate, and it had looked so tempting, hanging around the neck of the idol in Burma… were the members of the cult still searching for him, or had he finally shaken them from his trail? Together with his comrades, he had buried his cache of treasure in Tortuga, an island North West of Haiti, along with the necklace… did it really have a mysterious curse on it? All of them, to a man, had suffered horrible and gruesome deaths.

He stood up suddenly, the glass clattering to the floor. This solitude, this brooding… it was too much. He would seek out Father McNab; he must have peace in his soul. A swift hand movement, and the map disappeared into one of the hidden drawers in his bureau. Taking up his hat and his stick, he went out into the storm

The people in the field who saw him coming from the monastery in the morning dawn later recalled that the old villain looked happy and calm. And, when he shortly thereafter fell ill and died, with a grand funeral for the repose of his soul, maybe it was explained by the fact that the monastery inherited all of his money and his estate.

Only the furniture went up for auction: the chairs and the tables and the old bureau.