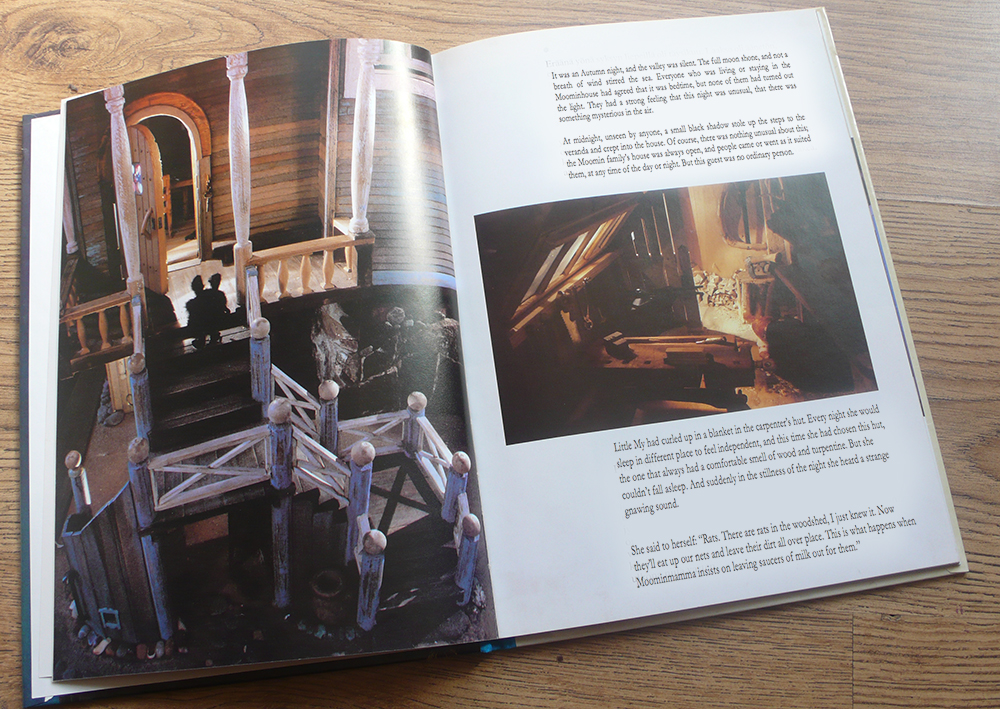

It was an Autumn night, and the valley was silent. The full moon shone, and not a breath of wind stirred the sea. Everyone who was living or staying in the Moominhouse had agreed that it was bedtime, but none of them had turned out the light. They had a strong feeling that this night was unusual, that there was something mysterious in the air.

At midnight, unseen by anyone, a small black shadow stole up the steps to the veranda and crept into the house. Of course, there was nothing unusual about this; the Moomin family’s house was always open, and people came or went as it suited them, at any time of the day or night. But this guest was no ordinary person…

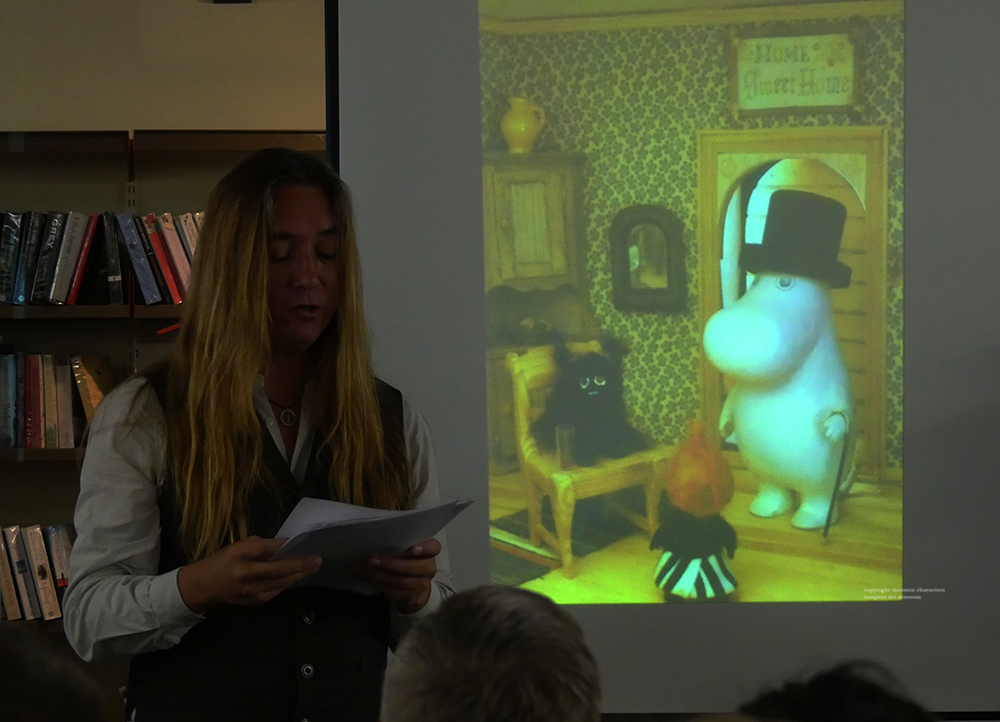

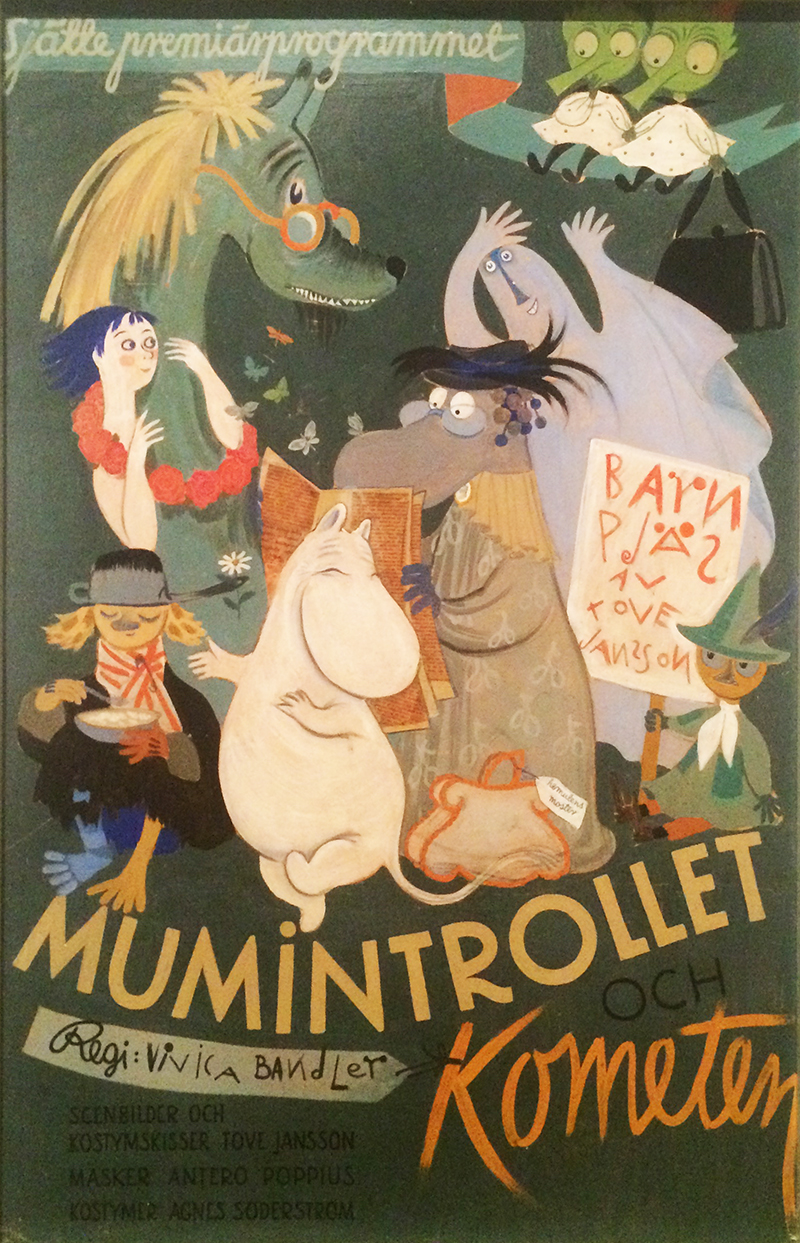

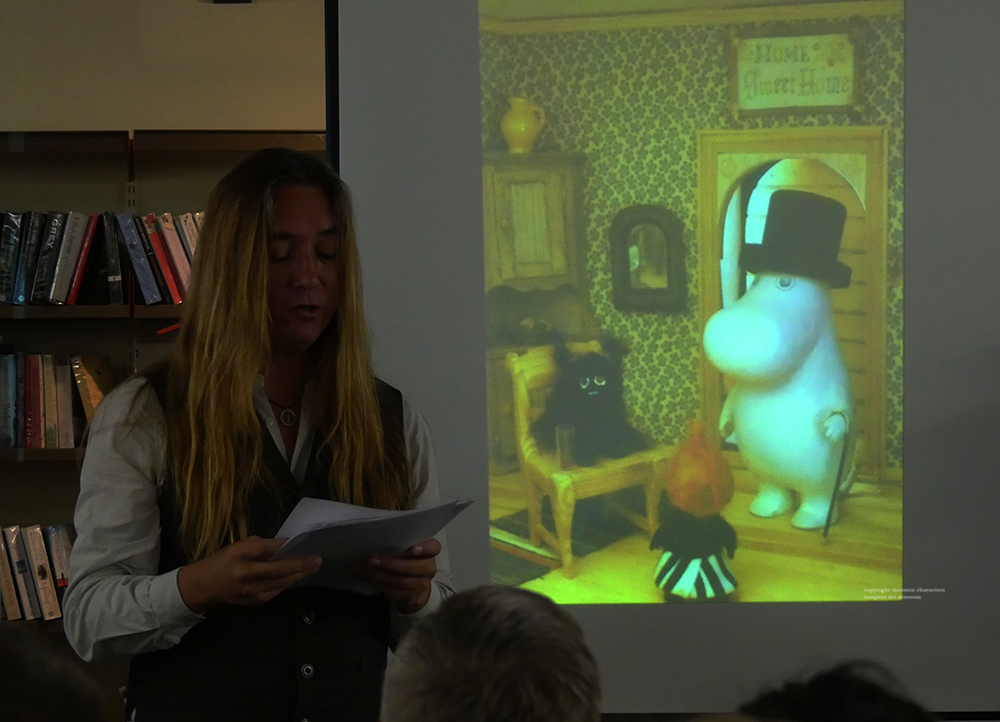

Thus begins Villain in the Moominhouse, the final Moomin tale and – until this week – unheard in English. I presented my translation at the ArchWay With Words book festival on September 25th, to a mixed crowd of adults and children from all over the place.

Translation is a funny process, often done by two people; one will undertake the vert translation, and the second will convert this into readable, flowing text. When I translated Villain just over a year ago, I found myself taking on both roles, and discovering a few challenges along the way.

First was finding a copy of the book. The 1980 impression is long out of print, and the 2000 reissue is also hard to find. But after scouring booksellers, I managed to find a copy of the latter. By pure chance, I stumbled upon a copy of the 1981 Finnish translation at a book sale in London, which gave me a second level of error checking.

I ran through the straight translations of both in about a week, and then the real work began: trying to recapture the writing voice of Tove Jansson.

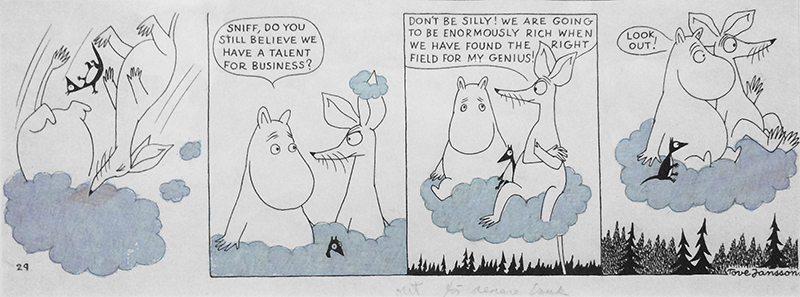

The English language Moomin stories were published over a quarter of a century, starting in 1946, and the tone of the writing strongly reflects not only the era, but the style of Tove Jansson herself. Although her ‘home’ language was Swedish – which uses grammatical genders – Tove Jansson made much use of the passive voice. This is inherent in Finnish and doubtless stems from growing up in Helsinki.

This carried on into the English versions of the books, particularly in the use of one as a gender-neutral pronoun, giving the books a slightly arch, archaic flavour.

Tove Jansson also kept tweaking her books. There have been several Swedish versions of the earlier books, resulting from her going back and rewriting a sentence or even a paragraph here and there, to reflect how the characters had changed after being shaped by later stories. The English translations remained (largely) unaltered, but I spent quite some time researching the originals to get the feel of the flow.

It’s worth learning Swedish just to read these stories in their original language. As great as they are in English, they are incredible in their original tongue.

Back to the translations. It took another few weeks before I was happy with my first draft. There were some decisions to make in terms of paraphrasing. The words skitar and kissa appear in the original text, referring to pooping and peeing respectively. They’re not in themselves offensive words in Swedish (well, not very), but very out of place in the English translation; use of either would have represented an anomaly in Moomin stories.

In the end, I used the following for Little My’s line:

She said to herself: “Rats. There are rats in the woodshed, I just knew it. Now they’ll eat up our nets and leave their dirt all over place. This is what happens when Moominmamma insists on leaving saucers of milk out for them.”

And when a terrified Moomintroll worries about needing the toilet:

“But what if they have to go and… well…” objected Moomintroll.

“Very well, then,” said Little My. “But they’ll have to go quickly.”

The Finnish translation was useful as a reference book, but some liberties had been taken with the translation itself – something that I’ve noticed in other Finnish translations of Tove Jansson’s work.

In the months following the preparation for the book festival I was, like Tove, tweaking the text incessantly, making final edits two hours before the curtain went up.

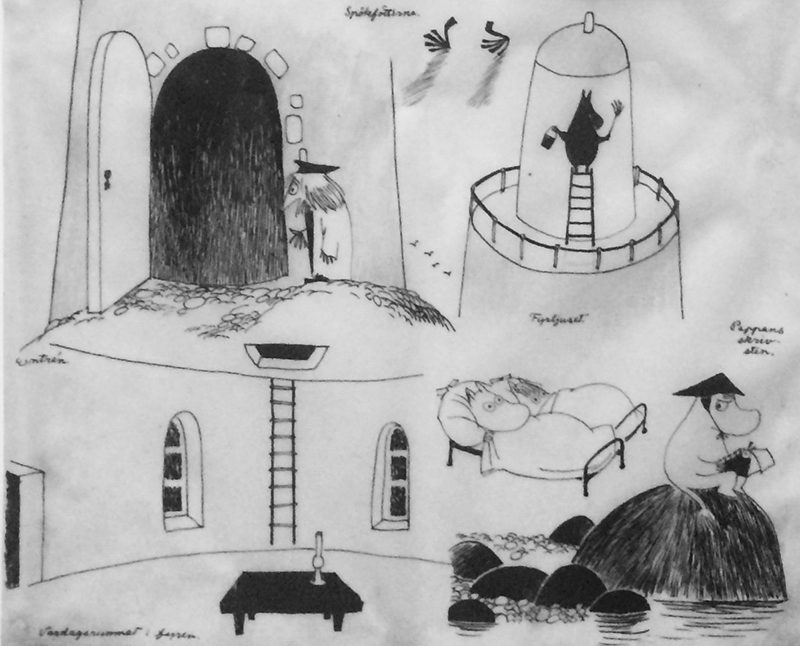

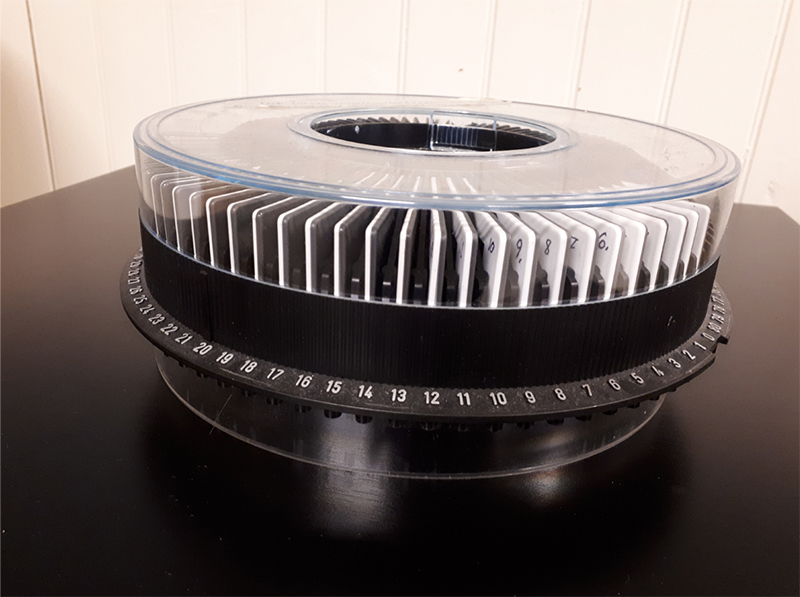

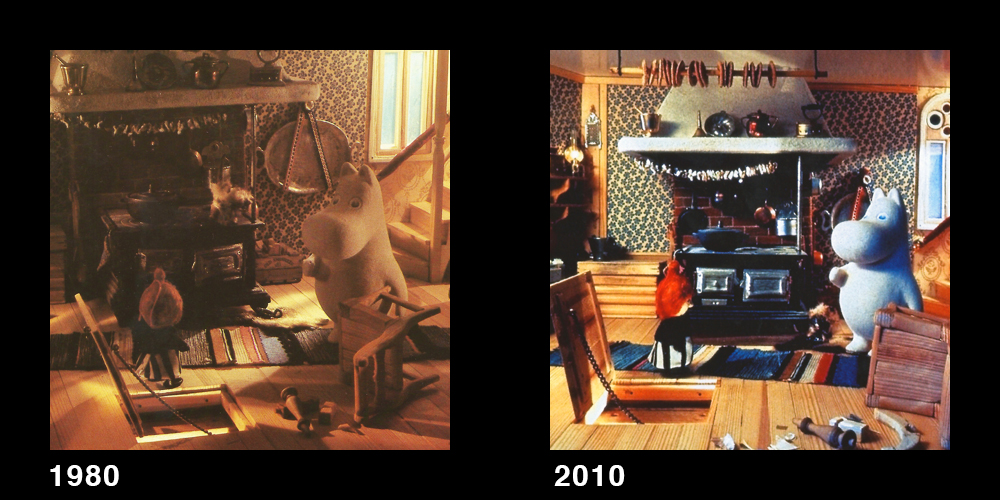

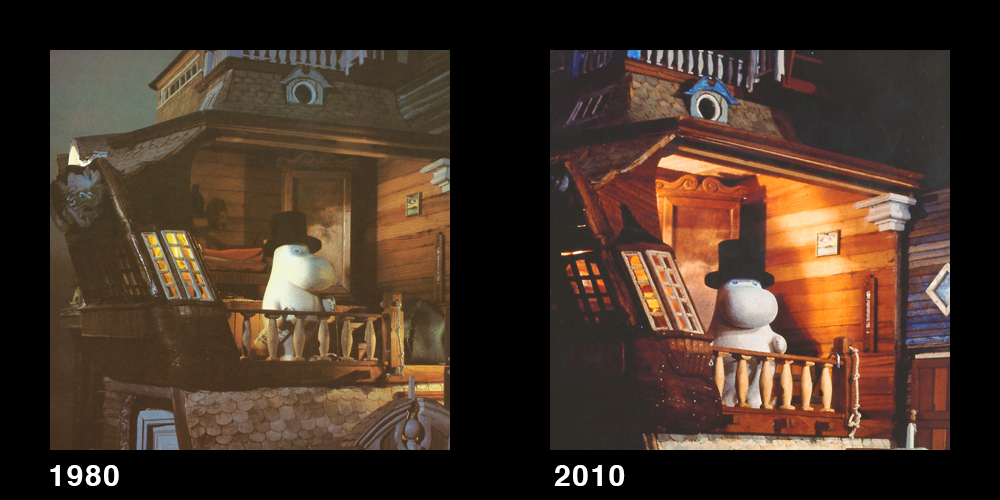

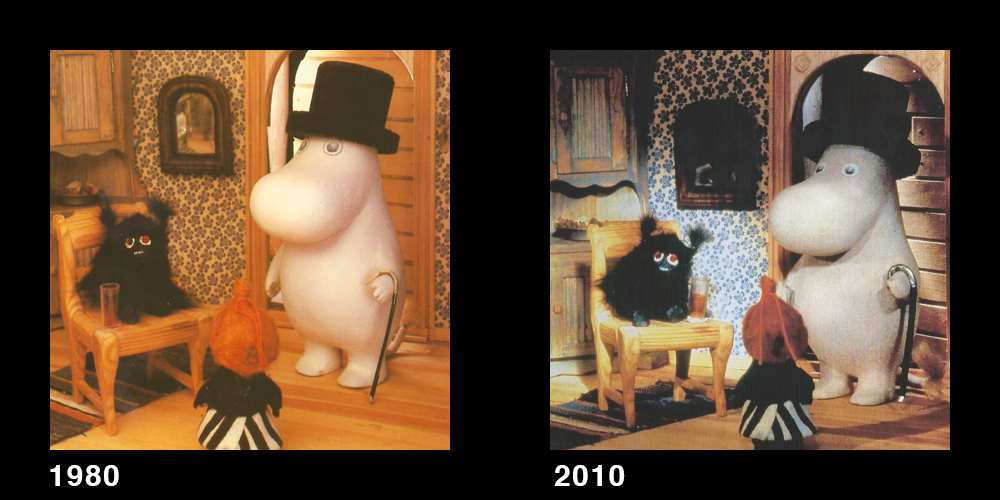

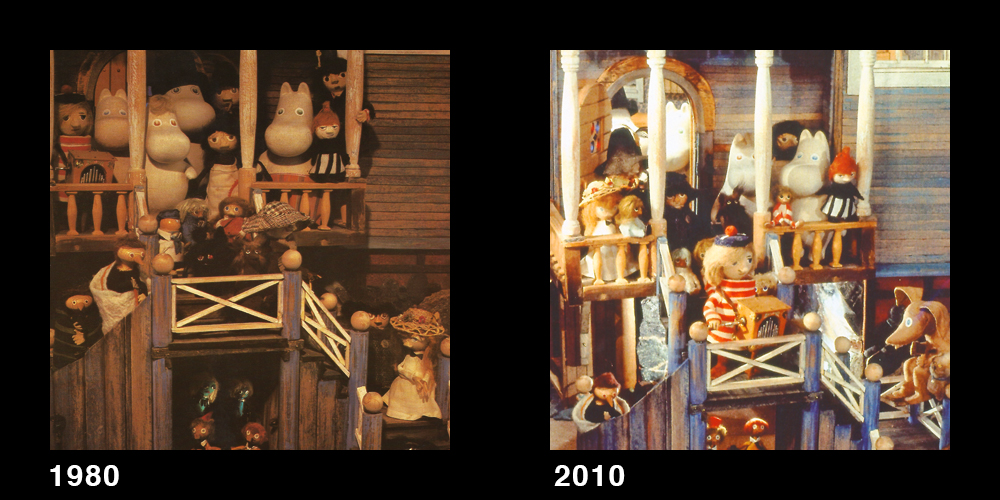

As Moomin stories go, it’s something of a diversion. The images (and I’ll talk about them in my next post) were not the usual illustrations; instead, they were photographs of the model characters in and around the vast model Moominhouse built by Tove and Tuulikki Pietila. The photos were taken by Per Olov Jansson, Tove’s brother.

It’s a short tale, one that wouldn’t be out of place in Tales from Moominvalley, and – without giving anything away – it answers the question of whether or not they eventually came home.

But a short story is just that, and in order to make for a full event, I included another two translations – not of Moomin stories, but of Tove’s earliest published works. Again, I’ll cover these in another post…